Has anybody ever thought what the other side of this digital age is? Well, Elizabeth Grossman, an environmental journalist discloses the latent veracity about the digital devices. Deep within every electronic device lie toxic materials that make up the bits and bytes, a complex thicket of lead, mercury, cadmium, plastics, and a host of other often harmful ingredients. Want to know more? Well, scroll down and have a glimpse to what the journalist have to say…

1. Who is Elizabeth Grossman in flesh and blood?

Elizabeth: I’m a third generation native of New York City who moved to Portland, Oregon ten years ago. I began writing full time in 1999, freelancing, writing about environmental and science issues – subjects I’ve been interested in since I began visiting the American Museum of Natural History as a child. The Pacific Northwest where the environment – the condition of rivers, forests, salmon and other native species – is an everyday issue, so this is a great place from which to be writing about these topics. My interest in what became “High Tech Trash” began with an investigation of water quality in the Willamette River, the river that flows through the city of Portland is which is about two minutes walk from my front door. I love to hike, go camping and paddling, to watch birds and sketch landscapes and the Northwest is a perfect place for getting out doing that. I also love to travel and am the kind of writer who likes to see what she’s writing about, so visit as many of the places I write about as I can.

2. Elizabeth, would you please shed some light on the evolution of tech recycling, the advantages of mining circuit boards instead of natural landscapes, and possibilities for a cleaner, healthier tech industry?

Elizabeth: As I understand it, interest in recycling high tech electronics began and is driven economically by interest in recovering metals – copper, precious metals that include gold and silver, and to some extent other metals. Mining companies quickly realized that it was more efficient, both in terms of money and natural resources, to mine a pile of old circuit boards than it would be to extract the equivalent amount of gold from raw ore from a mine, especially when you consider the great environmental costs of mining, both directly to the landscape and mining’s impact on local communities.

Copper as well as gold and other precious metals are essentially one hundred percent recyclable, meaning that they can be reused an infinite number of times. And right now, at current recycling rates, we are simply throwing away close to ninety percent of all these metals used in electronics. –Traditional desk top computers, with the big monitors (rather than flat screens) can contain as much as two to four pounds of copper, and have circuit boards that are between 30 and 50 percent metal.

And while there is far less than an ounce of gold in a computer, it’s valuable enough to make it worth recovering. So while there may someday be a way to make computers and other electronics without metal, when metal is necessary, it seems environmentally sensible to recover and reuse as much of this material as possible.

Plastics present a much greater recycling challenge than metals as there are so many different plastics used in electronics. They are often difficult to separate, and collecting sufficient quantities of a single type of plastic to put into reuse is also challenging. But getting plastics out of the waste stream and into new products is important as many of the current generation of plastics used most commonly in electronics contain chemicals that once released into the environment via disposal in landfills, open fires and incinerators are hazardous and toxic.

The leaded glass used in traditional monitors and televisions (ones that contain a cathode ray tube) can also be recycled but as flat screens begin to overtake CRTs in new equipment reusing leaded glass becomes more challenging, but there are uses for it in metals production, for example, and it should by all means be kept out of landfill as it contains not only lead, but also cadmium, barium and phosphorus.

3. Elizabeth, we would like to hear your experience in Sweden at the e-recycling plant?

Elizabeth: The interesting thing about the electronics recycling that takes place at the Boliden plant in Skelleftea, Sweden (this is up in the north on the Baltic, about two hours drive from the Finnish border), is that bits of old electronics – primarily circuit boards – are put into a smelter along with raw copper ore. The two streams of materials – electronics and ore – actually go into the same enormous cauldron where they are melted down and poured into molds to make new copper bars that end up as sheets of metal and wire and other new copper products. The used electronics are sorted and separated then shredded at a facility essentially next door to the smelter. These electronics come not just from Scandinavia but also from other recycling facilities all around the world, including the U.S. So that it’s entirely possible that an old Macintosh computer I once used could end up in a copper smelter in Sweden about 100 kilometers from the Arctic Circle.

4. What do you have to say about pop apart cell phone?

Elizabeth: I haven’t studied the pop apart cell phone in detail, but any innovations that make electronics easier to disassemble for refurbishing and upgrade for subsequent reuse or materials recovery is essential to diverting equipment from the waste stream. I’ve been told that removing the tiny mercury-bearing fluorescent lamp from a flat screen monitor can involve as many as 27 different screws. And dismantling my old iBook to remove its hard drive when I needed to send it for data recovery required downloading a 40-page manual. Clearly, these are bars to efficient recycling and reuse and anything that would improve the process and make it less labor-intensive is beneficial.

5. Who do you think is the leader in the world right now for responsibly dealing with the waste?

Elizabeth: Europe, the European Union, arguably has the most comprehensive laws regulating disposal of e-waste – and the EU’s e-waste regulation is accompanied by a law restricting the use of certain hazardous substances in electronics (standards which have quickly become virtually global), but Japan has also set up a national system for collecting used electronics for recycling which is mandatory, and other countries are following suit. As one of the world’s most prodigious users of electronics, the U.S., which still has no national regulation or system for collection and recycling lags conspicuously behind the EU and Japan.

6. What is your opinion on the Electronic Product Environmental Assessment Tool (EPEAT)?

Elizabeth: Overall, EPEAT seems like a very good start toward incorporating environmentally preferable features into electronics purchasing decisions. EPEAT is designed for large volume purchasers — companies and organizations and government that buy large quantities of equipment — but it would be great if this could be extended to small business and individual consumer purchasers. Anyone can make use of EPEAT criteria and make choices based on them, but ideally, these criteria would be universal. EPEAT criteria do not include a ban on use of prison labor for recycling. It does include restrictions on export of equipment and components for recycling but as with other similarly restricted exports, the question of enforcement remains. But EPEAT is new so it remains to be seen how what its actual impacts will be and if manufacturers will make additional improvements to achieve the highest EPEAT ratings for all equipment.

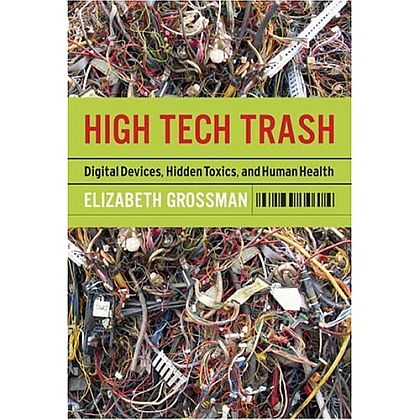

7. Could you please give us brief synopsis regarding your book High Tech Trash?

Elizabeth: What I decided to do in High Tech Trash was to explore the entire life cycle of high tech electronics, from extraction and processing of raw materials, through the manufacturing process to what happens to this equipment when we dispose of it. I wanted to make the connection between the natural world and the digital devices that have given us cyberspace, instant messaging and whole libraries of information, music and videos that appear on our computer screens, apparently out of thin air. This is an international story in every possible respect, because the manufacturing of materials and components that go into a single piece of equipment takes place on numerous continents, and when equipment is disposed of, it’s very likely that different materials will also end up in different countries and continents. In addition, the environmental impacts of resource extraction, manufacturing and disposal of electronics span the globe.

The book also looks at historical or legacy issues of pollution and health impacts of high tech manufacturing and at evolution of public policy regarding electronic waste.

I traveled over 50,000 miles working on the book, interviewed over 200 people, went down to the bottom of an underground mine (over a kilometer), wore lots of borrowed hard hats and safety glasses and saw, literally, acres of discarded computer equipment.

8. Do you think that current environment crisis is a result of lack of social responsibility or conscience?

Elizabeth: Wow. That’s a huge question. There are always some people, and I’ve spoken to a few, who say they simply don’t care, that what they can’t see or smell or feel, doesn’t concern them. But many more people, I think, certainly individually, actually want to do the right thing when it comes to the environment – to take care of their waste responsibly, to make decisions that will protect safe drinking water, clean air, safe food and to protect their families from harmful chemicals. Putting that into practice is, of course, another matter – and there are often many obstacles.

The current crisis, however, I think stems from a combination of decisions – some made long ago – that set us on the course of not incorporating the costs of waste (obsolete products, packaging, emissions, by-products, environmental destruction or health impacts) into those of production, and decisions in our choice of materials and design and production process. Some of these choices were due to lack of knowledge but others, I think, have been expedient – made to cut costs, rush products to market and to maximize profits. Both social responsibility and conscience were involved, I think, both in setting us on our present course and are involved in making changes needed to solve these problems.

9. Where you would like to take your fight, are there any set goals?

Elizabeth: I don’t really consider myself an activist on this issue in the sense that I don’t lobby, but based on my research it seems essential that everywhere that high tech electronics — computer equipment, cell phones, digital music and video devices, et al. — are used, whether it’s the U.S., India, Nigeria, China, Mexico or Kazakhstan, there should be some sort of system and infrastructure for dealing with this equipment at the end of its useful life. We also need to design equipment so that it does not contain toxic materials and in ways that ultimately cut back on the need to replace equipment so rapidly, and in ways that facilitate reuse and materials recovery. There needs, I think, to be regulation in place to prevent improper disposal of e-waste and export of e-waste to places where it will be handled or disposed of under environmentally and socially harmful and irresponsible conditions. Based on what I learned working on “High Tech Trash” it also seems clear that we need to revise our policies and regulations to better protect people and the environment from exposure to hazardous and toxic chemicals used in and to manufacture consumer products. That said, even since I began working on the book a few years ago, awareness of all these issues has grown tremendously and many positive changes have taken place. Much more still has to happen but lots of changes are underway.

10. Any parting words of advice, you’d like to give to our readers?

Elizabeth: When any of your digital devices become defunct, make sure it does not go into the trash. Use a manufacturer’s take-back program or a municipal one if it’s available (or a responsible recycler) to make sure the equipment goes into responsible reuse or recycling. Try to make your equipment last as long as possible, use it as efficiently as possible (energy, paper, etc) and for resource conservation’s sake, acquire only what you really need.

11. Finally, we would like to have your thoughts on the Instablogs News Network and all its related sites. Which one is your favorite?

Elizabeth: I have to confess that I hadn’t read or known of Instablogs News Network until you wrote to me earlier this month! I read dozens of articles from newspapers and magazines on-line everyday, so I’ve been a bit slow to find time for blogs. International news and articles from a non-US, non-European perspective are those I’d probably read most often on Instablogs because they would expand the points of view and perspectives I’m currently most frequently exposed to – particularly in politics and environmental issues.

Before signing off, I’d like to thank Elizabeth for sparing out her valuable time for this wonderful interview- which we had via email- and acquainting us with the tech recycling. Also, we’d like to wish her luck for all her future endeavors.